Contents

Summary

Introduction

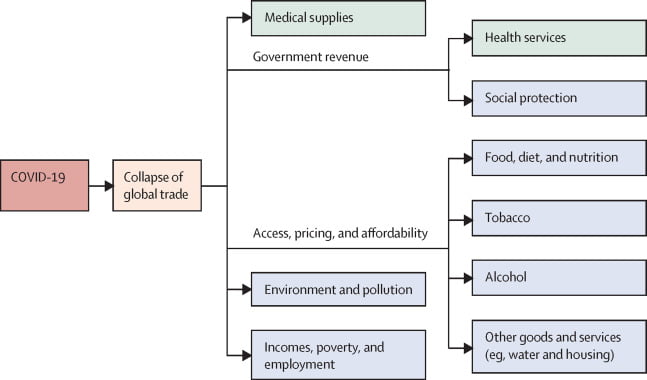

Although there has since been a partial rebound as lockdowns eased during summer in the northern hemisphere, total global merchandise trade for 2020 is forecast to fall by 9·2% in 2020, and a recovery to the precrisis trend is unlikely for several years. These changes to the global trading landscape have wide-ranging consequences for physical and mental health, as they affect supplies of drugs and medical equipment, nutrition and food security, and government income necessary to pay for health services.

In a world characterised by integrated and often just-in-time manufacturing processes, these actions caused marked reductions in the supply of manufactured goods, initially in China, but then elsewhere. Labour shortages at ports, caused by the pandemic, further slowed the movement of goods. Meanwhile, workplace closures in many countries and subsequent wage losses reduced demand for retail goods and traded services. Many of these trends are expected to continue as further lockdowns are introduced in response to second waves of infections.

The second mechanism is the economic effect. Although critics of trade liberalisation appropriately question whether the benefits of trade liberalisation are equally distributed between and within countries, it is widely accepted that many firms depend on trade to produce goods and services and to expand their sales and profits.

th sector

Access to medical supplies

For example, in the USA, individual states are bidding not just against each other but also against the federal government, thereby driving up prices.

These difficulties are especially acute in countries dependent on imports of medical products, such as Armenia, Brazil, and Colombia. Also, several countries have been unable to produce and export domestically manufactured equipment during the pandemic to protect domestic supply, leading to high procurement costs and delays elsewhere.

Trade restrictions have also constrained access to other basic health services, besides those needed to target COVID-19, including vaccines needed for mass immunisation campaigns.

These issues have been compounded by nationalist or regionalist approaches taken in many countries, including the USA, which have created a leadership vacuum and contributed to fragmented and uncoordinated pandemic responses.

Trade can be further facilitated by the actions of exporters. China, for example, has compensated for some of the collapse in demand for its non-medical exports by expanding exports of PPE and medical equipment.

There have also been calls for the incoming US administration to lift sanctions on Iran’s importation of medical supplies to help curb COVID-19 spread across the Middle East.

Other regions have also relaxed regulations to facilitate imports. The US Food and Drug Administration, for example, issued a new emergency use authorisation to permit the import of respirators made in China, Brazil, Europe, and elsewhere, which had not been previously authorised for sale.

Budgetary shortfalls

Typically, trade revenues expand the fiscal space needed to fund health systems in the absence of other tax sources, so any reduction in trade renders budgets vulnerable.

This effect has implications for progress towards WHO’s universal health coverage goal.

Second, economic recession in the wake of collapsing trade, and with it reductions in personal and business tax revenue, affects developed economies and adds further pressure in economies that are developing.

Similarly, concerns have been raised about how debt repayment delay schemes currently offered to low-income countries might impede progress towards universal health coverage, because the debt will not be cancelled and might even appreciate.

Thus, it is essential that these financial institutions recognise the harm that they can do, and adapt their policies accordingly.

These entities provide a buffer against the health consequences of economic hardship and social exclusion, so any decline in revenues and spending on social protection and public services is expected to undermine health, especially among families living in poverty or other precarious situations, and in economic systems that are already strained.

This risk reinforces the importance of adequate financing, with fair and effective conditions, in helping governments respond to the wider effects of COVID-19.

Employment and income

Equally, falling into poverty, losing work, and financial insecurity can result in physical and mental illness.

Other people at great risk include those living in border areas, especially if there is extensive cross-border trade.

The World Bank estimates that the contraction in global economic output as a consequence of the pandemic, and in particular the collapse of the many global supply chains on which workers in low-income and middle-income countries depend, will push between 88 million and 115 million people into extreme poverty in 2020.

Food security, nutrition, and unhealthy commodities

A loss of seasonal labour and the effect of supply-chain collapse on small farms in low-income countries is expected to have some negative consequences for outputs, whether for export or domestic markets.

In high-income countries, the effect on food outputs might be small, at least for staple products, because much food production is now mechanised and requires fewer workers than elsewhere.

One alternative cause is the growth of restrictions on agricultural trade. By Oct 18, 2020, 21 countries had announced temporary measures restricting food exports,

which has exerted upward pressure on prices. These controls are nevertheless rare, and most important will be the reduced incomes of people involved in sectors exposed to wider supply-chain collapse, because an adequate income is essential to sustaining access to enough food.

High-income countries are not exempt; in the USA, food insecurity has already doubled overall, and tripled among households with children.

Trade liberalisation during the post-war era has fostered the global diffusion of ultra-processed foods and their ingredients, sugary soft drinks and, with them, non-communicable diseases, such as obesity and diabetes.

In Canada, the amount of high-fructose corn syrup used in food production tripled after a 5% import tariff on the syrup was abolished as part of the North American Free Trade Agreement.

Similarly, the liberalisation of tobacco and alcohol trade stimulated rising consumption of these commodities globally.

Reduced trade could reduce consumption of these products and associated harms, yielding benefits to health.

Effect on environmental determinants

,

High-income countries are also major exporters of hazardous materials, such as electronic waste that releases toxicants, to low-income countries.

As trade declines, so too could the number of lives lost in low-income countries to the environmental harms created by fossil fuel emissions and toxic chemicals.

It will be necessary to return to past but failed efforts (eg, the Environmental Goods Agreement), and to find new ways of reconciling trade and environmental priorities, and to do so with strengthened global governance to ensure these opportunities are not squandered.

Towards an effective public health response

Several high-profile politicians and think tanks have already announced their support for further trade liberalisation to help the world recover from the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, such calls often take a narrow view of trade and health, either by assuming that aggregate economic gains translate into widespread improvements in human welfare, or by focusing specifically on medical and food supplies while overlooking other health determinants.

,

Between 1970 and 2006, over 40% of low-income countries had a net fall in total tax revenues that lasted more than 10 years after trade liberalisation, in part due to difficulties in levying domestic taxes to compensate for trade revenue declines following tariff cuts.

Increases in trade and economic growth stimulated by reduced tariffs did not necessarily compensate for the loss of revenue from those tariffs. Governments of low-income countries have long been advised to consider carefully the revenue implications of reducing tariffs, and to ensure first that alternative and non-regressive tax measures are in place to maintain health and social spending.

There is emerging evidence that companies seeking to maintain their sales in the context of collapsing trade are redoubling their efforts to limit these regulations, to support the economy. For example, several major processed-food exporters argued for Mexico to postpone its nutrition labelling regulations to help ease financial pressures caused by COVID-19.

However, the economic balance sheets of the unhealthy-commodity industries ignore the rising costs of treating those who fall ill from consuming their products.

,

For products that are harmful to health, maintaining or increasing the regulations that create trade and business costs might actually be a more effective route to long-term economic recovery, by reducing downstream health-care costs.

This reshoring can reduce some forms of the pollution from fossil fuel emissions that is generated by the international transportation of goods, thereby reducing climate change and particulate air pollution. However, it could simply shift the location of environmental damage and associated health harms, especially if reshoring is adopted by countries with relaxed environmental standards.

This risk underscores the importance of maintaining regulations that might create trade costs but which protect health and the environment, especially as economies recalibrate their trade relationships in response to COVID-19.

Conclusions

but also for governments, acting in the interests of their people, to reassess globalisation and design trade instruments that are conducive to good health. In doing so, they will need to recognise an explicit link between trade and health, something that should now be obvious, given how the initial spread of the disease occurred along established trade routes, as have many large-scale disease outbreaks throughout history.